The goal of EDC/HRE, Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education, is to enable and encourage young citizens to participate in their communities. The goal of democratic citizenship refers to a concept of democracy and politics. Democratic school governance plays a key role in EDC/ HRE, as it offers students opportunities to learn how to participate in a community. This unit therefore outlines these three concepts, as they are crucial for EDC/HRE as it is conceived in this manual.

1.1 Politics

1.1.1 Politics – power play and problem solving

Newspaper readers or TV news watchers will find that many media reports on politics fall into one of the following two categories:

- Politicians attack their opponents. In doing so, they may question their rivals’ integrity or ability to hold office, or deal with particular problems. This perception of politics – as a “dirty business” – makes some people turn away in disgust.

- Politicians discuss solutions to solve difficult problems that affect their country or countries.

These two categories of political events correspond to Max Weber’s classic definition of politics:

- Politics is a quest and struggle for power. Without power, no political player can achieve anything. In democratic systems, political players compete with each other for public approval and support to win the majority. Therefore, part of the game is to attack the opponents, for example in an election campaign, to attract voters and new party members.

- Politics is a slow “boring (of) holes through thick planks, both with passion and good judgement”.4The metaphor stands for the attempt to solve political problems. Such problems need to be dealt with, as they are both urgent and affect society as a whole, and are therefore complex and difficult. Politics is something eminently practical and relevant, and discussion must result in decisions.

Politics in democratic settings therefore requires political actors to perform in different roles that are difficult to bring together. The struggle for power requires a charismatic figure with powers of rhetoric and the ability to explain complex matters in simple words. The challenge of solving the big problems of the day, and our futures, demands a person with scientific expertise, responsibility and integrity.

1.1.2 Politics in democracy – a demanding task

Of course, we first think of political leaders who must meet these role standards that tend to exclude each other. There are prominent examples of leaders who stand for the extremes – the populist and the professor. One tends to turn politics into a show stage, the other into a lecture hall. The first may win the election, but will do little to support society. The second may have some good ideas, but only a few will understand them.

However, not only political leaders and decision makers face this dilemma, but also every citizen who wishes to take part in politics. In a public setting, speaking time is usually limited, and only those speakers will make an impact whose point is clear and easy to understand. Teachers will discover that there are surprising parallels between communication in public and communication in school – the scarcity of time resources, the need to be both clear and simple, but also able to handle complexity.

Exercising human rights – such as freedom of thought and speech, taking part in elections – is therefore a demanding task for all citizens, not only political leaders. In EDC/HRE, young people receive the training in different dimensions of competences, and the encouragement that they need to take part in public debates and decision making. As members of the school community, students learn how to take part in a society governed by principles of democracy and human rights.

1.1.3 The policy cycle model: politics as a process of solving problems in a community

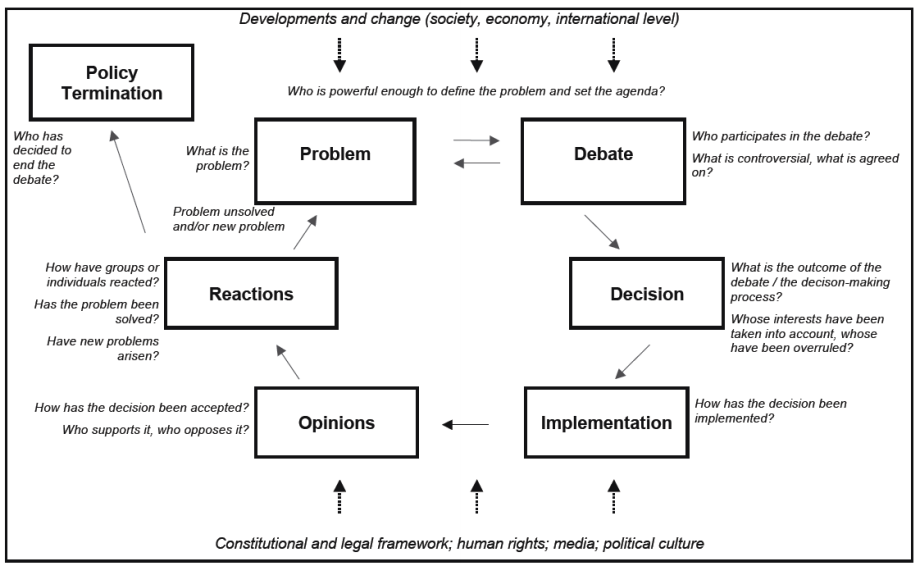

Politics is conceived as a process of defining political problems in a controversial agenda-setting process, and both in defining a political problem and excluding other interests from the agenda, a considerable element of power is involved. The model gives an ideal-type description of the subsequent stages of political decision making: debating, deciding on and implementing solutions. Public opinion and reactions by those persons and groups whose interests are affected show whether the solutions will serve their purpose and be accepted. Minorities or groups too weak to promote their interests who have been overruled may be expected to express their protest and criticism. If the attempt to solve a problem has succeeded (or has been defined as success-ful), the policy cycle comes to an end (policy termination); if it fails, the cycle begins anew. In some cases, a solution to one problem creates new problems that now must be seen to in a new policy cycle.

The policy cycle model emphasises important aspects of political decision making in democratic systems, and also in democratic governance of schools:

- There is a heuristic concept of political problems and the common good; no one is in a position to define beforehand what the common good is. The parties, groups and individuals taking part in the process have to find out and usually agree to compromise.

- Competitive agenda setting takes place; in pluralist societies, political arguments are often linked to interests.

- Participation is imperfect in social reality, with certain individuals and groups systematically having less access to power and decision-making processes, thus being a model that requires attention to increasing the access of less powerful.

- Political decision making is a collective learning process with an absence of omniscient players (such as leaders or parties with salvation ideologies). This implies a constructivist concept of the common good: the common good is what the majority believes it to be at a given time.

- There is a strong influence of public opinion and media coverage – the opportunity for citizens and interest groups to intervene and participate.

The policy cycle is a model – a design that works like a map in geography. It shows a lot, and deliv-ers a logic of understanding. Therefore models are frequently used in both education and science, because without models we would understand very little in our complex world.

We never mistake a map for the landscape it stands for – a map shows a lot, but only because it omits a lot. A map that showed everything would be too complicated for anyone to understand. The same holds true for models such as the policy cycle. Nor should this model be mistaken for reality. It focuses on the process of political decision making – “the slow boring of holes through thick plants” – but pays less attention to the second dimension of politics in Max Weber’s definition, the quest and struggle for power and influence.

In democratic systems, the two dimensions of politics are linked: political decision makers wrestle with difficult problems, and they wrestle with each other as political opponents. In the policy cycle model, the stage of agenda setting shows how these two dimensions go together. To establish an understanding of a political problem on the agenda is a matter of power and influence.

Here is an example. One group claims, “Taxation is too high, as it deters investors,” while the second argues, “Taxation is too low, as education and social security are underfunded.” There are interests and basic political outlooks behind each definition of the taxation problem, and the solutions implied point in opposite directions: reduce taxation for the higher income groups – or raise it. The first problem definition is neo-liberal, the second is social democrat.

Citizens should be aware of both. The policy cycle model is a tool that helps citizens to identify and judge political decision makers’ efforts to solve the society’s problems.

4. Weber M. (1997), Politik als Beruf (Politics as a vocation), Reclam, Stuttgart, p. 82 (translation by Peter Krapf).

1.2 Democracy

1.2.1 Basic principles

In Abraham Lincoln’s famous quotation (1863), democracy is “government of the people, by the people, for the people”; the three definitions can be understood as follows:

- “of”: power comes from the people – the people are the sovereign power that exercises power or gives the mandate to do so, and whoever is part of authority may be held responsible by the people;

- “by”: power is exercised either through elected representatives or direct rule by the citizens;

- “for”: power is exercised to serve the interests of the people, that is, the common good.

These definitions can be understood and linked in different ways. Political thinkers in the tradition of Rousseau insist on direct rule by the citizens (identity of the governed and the government). The people decide everything and are not bound by any kind of law. Political thinkers in the tradition of Locke emphasise the competition between different interests in a pluralist society; within a constitutional framework, they must agree on a decision that serves the common good.

No matter how long the democratic tradition is in a country and how it has developed it cannot be taken for granted. In every country, democracy and the basic understanding of human rights have to be permanently developed to meet the challenges that every generation faces. Every generation has to be educated in democracy and human rights.

1.2.2 Democracy as a political system

Core elements of modern constitutional democracies include:

- a constitution, usually in written form, that sets the institutional framework for democracy protected in some countries by an independent, high court; human rights, usually not all, are protected as civil rights;

- human rights are referred to in the constitution and then relegated to civil rights as guaranteed constitutionally. Governments that have signed human rights conventions are obligated to uphold the range of rights they have ratified, regardless of whether they are specifically referred to in the constitution;

- the equal legal status of all citizens: all citizens are equally protected by the law through the principle of non-discrimination and are to fulfil their duties as defined by the law.

- universal suffrage: this gives adult citizens, men and women, the right to vote for parties and/ or candidates in parliamentary elections. In addition, some systems include a referendum or plebiscite, that is, the right for citizens to make decisions on a certain issue by direct vote;

- citizens enjoy human rights that give access to a wide range of ways to participate. This includes the freedom of the media from censorship and state control, the freedom of thought, expression and peaceful assembly, and the right of minorities and the political opposition to act freely;

- pluralism and competition of interests and political objectives: individual citizens and groups may form or join parties or interest groups (lobbies), non-governmental organisations, etc. to promote their interests or political objectives. There is competition in promoting interests and unequal distribution of power and opportunities in realising them;

- parliament: the body of elected representatives has the power of legislation, that is, to pass laws that are generally binding. The authority of parliament rests on the will of the majority of voters. If the majority in a parliamentary system shifts from one election to the next, a new government takes office. In presidential systems the head of government, the president, is elected separately by direct vote;

- majority rule: the majority decides, the minority must accept the decision. Constitutions define limits for majority rule that protect the rights and interests of minorities. The quorum for the majority may vary, depending on the issue – for example, two-thirds for amendments to the constitution;

- checks and balances: democracies combine two principles: the authority to exercise force rests with the state, amounting to a “disarmament of citizens”.5 However, to prevent power of force to turn into autocratic or dictatorial rule, all democratic systems include checks and balances. The classic model divides state powers into legislation, executive powers, and jurisdiction (horizontal dimension); many systems take further precautions: a two-chamber system for legislation, and federal or cantonal autonomy, amounting to an additional vertical dimension of checks and balances (such as in Switzerland, the USA or Germany);

- temporary authority: a further means of controlling power is by bestowing authority for a fixed period of time only. Every election has this effect, and in some cases, the total period of office may be limited, as in the case of the US president, who must step down after two four-year terms of office. In ancient Rome, consuls were appointed in tandem, and left office after one year.

1.2.3 A misunderstanding of human rights and democracy

Democracy is based on the standards and principles of human rights. Human rights are sometimes misunderstood as a system in which the individual enjoys complete freedom. This, however, is not the case.

Human rights recognise individual rights and liberties, which are inherent in being human. However, these rights are not absolute. The rights of others must also be respected, and sometimes there will be conflicts between rights. Democratic processes help to set up processes that facilitate the freedom of people, but also set necessary limits. In an EDC/HRE class, for example, a discussion is held. To give all students the opportunity to express their opinion, speaking is rationed, maybe quite strictly. For the same reason, speaking time is limited in parliamentary debates or TV talk shows.

Many rules in the highway code limit our freedom of movement: speed limits in town, having to stop at red traffic lights, etc. Clearly these rules are in place to protect people’s life and health.

Democracy gives more freedom to the people, and also to individuals, than any other system of government – provided it is set in an order, that is, an institutional framework, and implemented as such. To function well, democracy relies on a strong state that exercises the rule of law and achieves an accepted degree of distributive justice. A weak state, or weak rule of law, means that a government is not able to carry out its constitutional framework and laws.

1.2.4 Strengths and weaknesses

Broadly speaking, the different types of democracies share some strengths and weaknesses including the following.

a. Strengths of democracies

- Democracy provides a framework and means for civilised, non-violent conflict resolution; the dynamics of conflict and pluralism support the solution of problems.

- Democracies are “strong pacifists” – both in their societies and in international politics.

- Democracy is the only system that facilitates an exchange of political leadership without changing the system of government.

- Democracies are learning communities that can accommodate human errors. The common good is defined by negotiation, not imposed by an autocratic authority.

- Human rights reinforce democracies by providing a normative framework for political processes that is based on human dignity. Through ratification of human rights treaties, a government can extend to its citizens “promises” that maintain personal liberties and other rights.

b. Problems and weaknesses

- Parties and politicians tend to sacrifice long-term objectives for success in elections. Democracies create incentives for short-sighted policy making, for example at the expense of the environment or later generations (“muddling through”).

- Government for a people is government within the confines of a nation state. Increasing global interdependence, such as in economic and environmental developments, limits the scope of influence of democratic decision making in a nation state.

1.2.5 Conclusions

Democracies depend on their citizens to what extent the strengths of democracies are unfolded and their weaknesses are kept in check. Democracies are demanding systems, depending on their citizens’ active involvement and support – an attitude of informed and critical loyalty; as Winston Churchill (1947) put it, “Democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”

Both in established and in young democratic states, EDC/HRE contributes decisively to the political culture that democracies must be rooted in to thrive and survive.

5. There is a notable example in which the principle of disarming citizens is modified, namely the USA.

1.3 Democratic governance of schools

1.3.1 School – a micro democracy?

Education for democratic citizenship and human rights education (EDC/HRE) is based on the core principles of teaching through, about and for democracy and human rights in school. School is conceived as a micro-community, an “embryonic society”6 characterised by formal regulations and procedures, decision-making processes, and the web of relationships influencing the quality of daily life.

Is school then to be conceived as a miniature-size democracy? A glance at the list shows that schools are not small states, in which elections are held, teachers enact like governments, head teachers resemble presidents, etc. Therefore the question may be dismissed as rhetorical. So what can schools do for EDC/HRE?

1.3.2 Democratic school governance: four key areas, three criteria of progress

Elisabeth Bäckman and Bernard Trafford, head teachers in Sweden and the UK and authors of the Council of Europe manual “Democratic governance of schools”,7 have explored this question in depth. Schools, they argue, require both management and governance. School management is school administration – for example, the implementation of legal, financial and curricular requirements. The relationship between the head teacher and students is hierarchical, based on instruction and order. School governance, on the other hand, reflects the dynamics of social change in modern society. Schools need to interact with different partners and stakeholders outside school, and to answer problems and challenges that cannot be foreseen. Here, all members of the school community, includ-ing first and foremost the students, have an important role to play. The members of the community interact, negotiate and bargain, exercise pressure, make decisions together. No partner has complete control over the other.8

Bäckman and Trafford suggest four key areas for democratic school governance:

- governance, leadership and public accountability;

- value-centred education;

- co-operation, communication and involvement: competitiveness and school self-determination;

- student discipline.

Bäckman and Trafford apply three criteria based on the Council of Europe’s three basic principles of EDC/HRE, to measure progress in these key areas:

- rights and responsibilities;

- active participation;

- valuing diversity.

1.3.3 Teaching democracy and human rights through democratic school governance

Bäckman and Trafford provide a detailed set of tools to meet the task of teaching and living out democracy and human rights in the whole school. Students experience democratic participation in school, but schools remain institutions for education; they are not turned into would-be mini-states although they are mini-societies.

6. See Dewey J. (2007), The School and Society, Cosimo, New York, p.32.

7. Bäckman E. and Trafford B. (2007), Democratic Governance of Schools, Council of Europe, Strasbourg.

8. Ibid., p.9.

You are reading Volume I

You are reading Volume I