2.1 Task

In the course of planning your lessons and teaching units, one aspect which deserves attention is the question of how to control and ensure the students’ progress in learning, how to identify the progress they have made, and how to evaluate the results of the students’ learning and your teaching activities. Before the lessons take place, therefore, you must plan how to establish or estimate, and improve the effect and quality of your teaching, and how to record, analyse, improve and judge the students’ work and learning activities. In doing so, you will consider by what measures and instruments you will be able to find out to what extent the class as a whole or individual students have achieved the set objectives and, if required, on what criteria you will base your grading system.

In this chapter you will find out about assessment of students, of teachers and of the school as a whole.

2.2 Key questions

Learning process of students:

- How is successful learning identified and assessed?

- In what way is self-assessment and assessment by others applied?

- How do I ensure that the students have achieved the objectives?

- Did the students regularly experience success while they were learning?

- Are they aware of the progress they have made?

- Does my teaching give boys and girls an equal chance of success?

- Do the students consciously watch, control and improve their learning and working behaviour?

- Were the students given any guidelines to assist them while learning?

- Can the students control and assess their learning behaviour and their results themselves?

- Can the students identify the learning behaviour of other colleagues through peer evaluation?

- In their self-assessment, do the students also refer to their own objectives, standards, criteria or needs?

- Do I perceive individual students’ progress?

- How do I identify learning problems of individual students?

- How do I observe social interaction in the class?

- How do I keep a record of my observations and assessments of individual students and the class as a whole?

Learning process of teachers:

- How is successful learning identified and assessed?

- In what way is self-assessment and assessment by others applied?

- How, when and with whom do I reflect on my teaching?

- How do I let my students participate?

- How do I relate my students’ success or failure to my teaching?

- How do I recognise my progress in teaching, and how do I learn as a teacher?

2 - Work file 1: Different dimensions of assessment

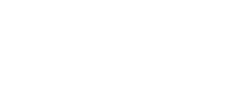

The different dimensions of students’ assessment include three levels. By using this cube model, the interdependence of the three dimensions can be explained.

Dimension 1 – perspectives: students can assess themselves (self-assessment) or they can be assessed by others (assessment by others).

Dimension 2 – forms: assessment can have three different forms – assessment of learning processes, assessment of learning achievements and prognostic. Each form has advantages and disadvantages.

Dimension 3 – standards of reference: for assessment a teacher can orient himself/herself on an individual standard (the student), on an objective standard (learning goal) or on a social standard (position of student in class). It depends very much on the standard of reference what impact assessment has on the future learning of the student.

Before we start reflecting upon the different dimensions we have to ask ourselves what competences we assess. In EDC/HRE this question is answered by the three competences already discussed: competence of analysis, competence of political reasoning and action competence.

In this respect we can also raise the following questions which revolve around the aspect of setting clear and objective criteria for evaluating and assessing:

- Is it the essentials which are tested in the assessment of students’ performance (permanently stored information, facts of exemplary importance, and in excess of mere knowledge of facts, “the tools of thought and action”, skills and abilities)?

- In marking the students’ work, are the marks defined by unbiased criteria?

- Do the standards of performance in the test correspond to those of the syllabus?

- Have all the requirements which have to be met to achieve a certain mark been determined beforehand (different levels of achievement)?

- Does the test also enable the students to understand which parts of a learning objective they have achieved?

- Have different types of testing been developed for students with different starting conditions?

- Can the students carry out the tests individually where this seems appropriate (for example, can they choose the exact point in time)?

2 - Work file 2: Perspectives of assessment

Internal and external assessments enable a person to get a picture about his/her own status of learning and to develop further steps on the way. Both kinds of assessment also help to set new goals.

All people are used to assessment by other people. By being assessed by other people one receives feedback from students, teachers or parents.

Self-assessment describes the ability to estimate oneself and to draw the consequences thereof. It is an essential instrument to support learners in their autonomy and to guide them out of the pure dependence on teachers’ feedback. Students who are able to estimate themselves realistically develop a better picture of their own self and will be less endangered to feel insecure. They will be less dependent on feedback and praise and can interpret reactions of teachers more adequately.

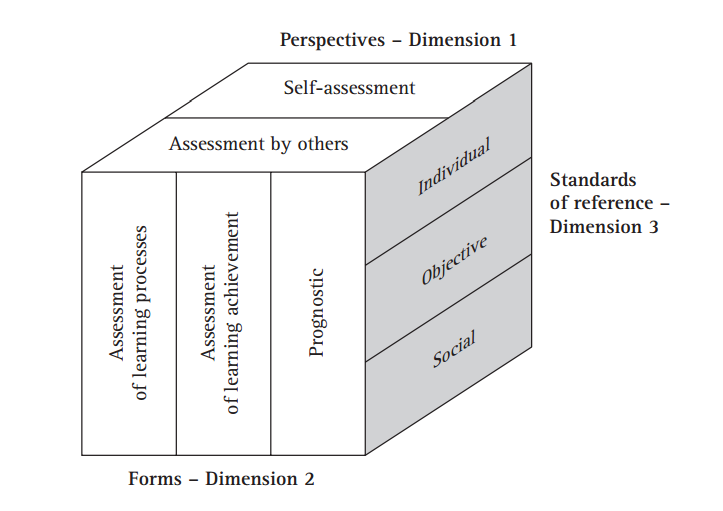

Self-assessment and assessment by others do not have to be congruent completely but should be heard in joint meetings, thought over and discussed. A student does not see herself/himself automatically in the same way the teacher does. Different viewpoints have to be laid out and discussed. Thereby, blind spots, narrowed perspectives or fixed pictures can be corrected. Students have to learn step by step how to estimate their own competences and abilities as well as how to give feedback to other students, how to accept feedback and discuss it. Through this step-by-step approach self-assessment and assessment by others become more congruent.

2 - Work file 3: Perspectives and forms of assessment

Assessment of learning processes (formative)

This perspective serves to improve, control and check on a student’s learning process, or the student’s and teacher’s activities to achieve a certain objective.

Assessment of learning achievements (summative)

At a certain point in time, a conclusive assessment sums up the knowledge and skills that a student has acquired. Its main purpose is to inform, for example, the student or parents about the student’s level of performance.

Prognostic assessment

This type looks at a student’s future development. At different stages during a student’s school career, people involved in a student’s education process (students, teachers, parents, in some cases school psychologists and authorities) recommend how a student should continue his or her school career.

Assessment of learning processes

The main goal in the assessment of learning processes (or formative assessment) is to support the individual student. Thus, efficiency of teaching is improved. Instead of fighting the symptoms the underlying reasons for learning difficulties are being investigated and are being tackled (these reasons can be cognitive as well as emotional). Mistakes are not corrected but analysed. In this way the ideas and mindset of a student can be understood and supported in a goal-oriented way. Difficulties have to be discussed together with the student and can be dealt with by using special support measures or tasks. By analysing the source of mistakes, students do not have to adapt superficially. By analysing these sources of mistakes, students do not feel at the mercy of their difficulties. Instead, they learn how to develop individual strategies for facing their problems.

In this respect successful learning means a continuous steering of the learning process and working on mistakes by both – teacher and student – and not merely the search for the best methods.

Possibilities of assessment of learning processes:

- observations;

- small, everyday tests;

- tests after a long working phase.

Tests that assess learning processes act as an indicator for the teaching and learning process. They enable the students as well as the teachers to check the level of achievement. Gaps and insecurities can be filled with additional tasks.

Possibilities of testing:

- observing students while solving a task;

- accurate viewing and analysis of the completed tasks;

- individual conversations about completed tasks;

- asking questions about the way a problem was resolved;

- short tests.

Out of observations and conversations about the way of working on tasks and about the sources of mistakes individual goals arise that the students set themselves, that they work out together with the teacher or that the teacher can set for them.

When applying this kind of assessment in our teaching, the logical consequence is also a shift towards:

- goal-oriented learning instead of purely content-oriented learning;

- individualised teaching instead of teaching where everybody works on the same task.

Assessment of learning achievements

Assessment of learning achievements (or summative assessment) gives an evaluation of a student’s achievement in a nutshell. It sums up all acquired knowledge and competences. It acts as an instrument of feedback to the parents, the students and the teachers. It can be the basis of a goal-oriented support.

These kinds of assessments are used after long sequences of teaching and learning through observation and tests. They inform the different addressees to what degree the students have reached the different goals. Examples of assessment of learning achievements are all kinds of tests that ask for the students’ accumulated knowledge or competences of a certain subject area over a certain period of time (for example, democracy quizzes, maths tests, vocabulary tests, social studies tests). Assessment of learning achievements is commonly used in schools in all subjects. Even though they are necessary for grading the students and give the teacher selective information about the students’ overall performance, they bear various problems.

As a means of feedback grades are used. In connection with grades there are several unsolved problems:

- Different teachers evaluate the same student’s product differently. Assessment is not objective. In this respect it is not relevant which subject it is. A maths test will be evaluated as differently by different teachers as a written story. Thus, assessment is strongly influenced by the teacher who evaluates. It can be a question of faith for a student and his or her individual future school career in which class and with which teacher he or she spends his/her school time. It can be stated that objectivity is not fulfilled as a criterion.

- A teacher tends to evaluate the same work of a student differently at different points in time. Assessment is not reliable. No matter which subject is the object of assessment, a teacher will evaluate differently at different points in time. It can be stated that the criterion of reliability is not fulfilled.

- It is not clearly defined what is expressed through a grade (skills, competences, knowledge, attitudes?). When teachers use grades in their assessment of achievements they integrate various aspects into the given grade, such as effective achievement in the past semester, estimated achievement ability, learning progress or deterioration in comparison to the class average and motivational, as well as disciplinary aspects. It is very difficult for the student to really find out what the given grade stands for. Usually, students do not know about the different assessment strategies of their teachers. Contents can be multidimensional and the space for interpretation can be big. Bearing in mind the different functions of grades in our society such as qualification, selection and allocation, interpreting given grades gets even more complex. It can be stated that the criterion of validity is not fulfilled. For most of the above functions grades according to an assessment of learning achievements are not usable indicators for future school, study or professional success.

- The common practice of grading according to an assessment of learning achievements has got a very important undesired effect: giving grades within a class according to a normal distribution leads to even more experiences of failure for the academically weaker students. Because the few places in a normal distribution for the very good and good ones are reserved for the same students, the same students will always remain on the other end of the scale. Even if they improve their academic achievement they will still remain at that end. Therefore, ranking the students according to their measured performance within the class will only lead to demotivation and loss of interest as situations remain unchangeable, especially for the weaker ones.

- Grades are not applicable to certain situations or phenomena: it may be simpler in subjects like mathematics to come to a right or wrong answer but it becomes more difficult in arts subjects or any other creative area of learning as well as language. This is due to missing or unclear criteria for evaluation and due to the fact that different subjects trigger different competences or skills. In EDC/HRE the discussion of different forms of solving a problem may lead to very creative or innovative ideas whereas in other subjects only one answer can be viewed as the correct one. So, there is the danger that grades, and the wish to be able to grade everything in an assessment of learning achievements method, can lead to uniformity. A creative search for new ways of solving the task cannot take place.

- Grading arithmetic is mathematically not valid: ideally, grades can be not more than rough estimates for an approximate rank of a student within his or her class. In this respect, even very accurate mathematical methods cannot serve as a means for improving this situation. Calculating the average of a grade by adding different grades and dividing again by the number of grades given can only serve as an additional source of security in a superficial way. It also depends on the time a grade was given. A student who started off the semester with a rather low grade and improved during the time should be evaluated differently from a student whose grades deteriorated during the semester. Even though the calculated average might be the same, the status of achievement and learning progress of these two students are not.

Following the above-mentioned problems, assessment of learning achievements should not be the only way of collecting information about the students’ performance in EDC/HRE. Competences and skills that have been acquired by the students should also be measured by applying methods of formative assessment.

Prognostic assessment

Prognostic assessments act as a means of estimation and prediction of the future career. Prognostic assessment combines basic aspects taken from an assessment of learning processes and an assessment of learning achievements and tries to formulate a diagnosis for the student’s future. It asks questions like: how can we support the individual development and the positive learning processes? Prognostic assessments become very important at different stages in a student’s academic life:

- school enrolment;

- repetition of a year;

- switching classes/schools;

- transfer to a different type of school (for example, special education);

- transfer to a higher school.

In this respect discussions have been going on for the past decades as to whether prognostic assessment can really be described as a form of assessment or can rather be viewed as a function of assessment.

2 - Work file 4: Standards of reference

There are three different basic standards of reference for the assessment and marking of students’ performance:

- Individual criterion: the student’s present performance is compared with his or her previous work.

- Objective criterion: the student’s performance is compared with the learning objectives that have been defined.

- Social criterion: a student’s performance is compared with that of the students within the same class or the same age group.

|

Type of criterion |

Individual criterion |

Objective criterion |

Social criterion |

| Reference figure | Learning progress | Learning objective | Normal curve of distribution, arithmetic average, deviation |

| Information | How much has been learned between time 1 and time 2? | To what extent has the student approached the learning objective? | How big is the deviation of the individual progress from the average? |

| Type of assessment | Tests, verbal assessment, learning progress report, structured form of observation | Goal-oriented test, learning progress report, structured form of observation | Test including a grade oriented on the average of the class |

|

Pedagogical implication |

Very high | Very high | Is often used for selection; is not important for orientation towards support for students |

2 - Work file 5: Assessment of students – the influence of assessment on self-concepts

Assessment in school is a wide-open field. It not only has influence on explicit things that can be observed such as students’ qualifications, their positioning in society because of grades and thus their academic career. Assessment in school also has influence on other aspects within the individual such as self-image, self-esteem and the general concept one has about his or her own competences and abilities. School has got enormous influence on the self-concept of competences. Its direct influence depends on the way assessment is chosen and carried out in school.

Social criterion

Because of the social context in which learning in school takes place, using the social criterion as a measure can give essential information about competences in comparison to other students. At the same time estimates about competences in a comparative social perspective strongly influence the self-image and self-concept of students.

Individual criterion

Using the individual criterion for assessment means comparing intra-individual differences with each other. What is the difference between the student’s achievement in EDC/HRE last month and now? It is a temporary comparison that is used here. Young students especially tend to prefer this criterion as a tool for assessment. The amount of “added value” is being recorded over a certain amount of time. This makes it possible to give feedback to the student about the range of his or her achievement as well as the way in which it has increased or decreased. Achievement is not compared to the achievement of other students. It is the progress which is in the focus. This way of assessment also corresponds with the informal learning processes that take place out of school where the student evaluates his or her own competences autonomously.

Objective criterion

Academic achievement is being compared with a learning objective. An individually achieved learning progress is being compared with a realistically reachable goal. This way of assessment is an objective-based norm and informs about the approach to a goal which is defined as the perfect achievement. Comparing the student’s achievement with other students’ learning progress is not of importance. Criteria-based tests are oriented towards clearly defined goals. They measure the achievement with reference to a certain characteristic decided by the teacher. This also means that the teacher has to set and present the goals the students have to approach in their achievement. Thus, achievements of the student will not be compared to the ones of other students. According to various studies in this field, social processes of comparisons between students only start when there is no objective criterion used in assessment.

What are the results of this discussion? If a teacher wants to strengthen the self-image and self-concept of his or her students, assessment should happen following an objective criterion. Goals given by the teacher have to be clear and have to be communicated to the students.

2 - Work file 6: Checklist “How do I assess my students?”

When assessing students teachers should bear in mind the key principles in the following checklist:

- Assessment should be a means of support: help for individual defining of position, hints for further work, strengthening the self-concept and self-image of students.

- Assessment should help students and enable them to evaluate themselves.

- Assessment has to be transparent: students have to know the basis of assessment, the criteria of assessment as well as the norms used.

- Assessment has to be adequate to the contents and goals. Knowledge has to be evaluated differently from competences and skills.

- Teachers have to bear in mind the function of selection they fulfil when grading. Instead of only summary assessment, conversations and reports should become the future methods and tools of assessment. Only by doing so can permeability within the school system be improved.

- Tests should be designed in a way that they test the approach towards the set goals. (Tests also give information about the quality of the teaching which was used for approaching these goals: test results therefore not only give information about the students’ performance but also about the quality of the teacher’s teaching.)

Questions for self-evaluation

Learning process of the students:

- How do I ensure that the students have achieved the objectives?

- Did the students regularly experience success while they were learning?

- Are they aware of the progress they have made?

- Does my teaching give boys and girls an equal chance of success?

- Do the students consciously watch, control and improve their learning and working behaviour?

- Were the students given any guidelines to assist them while learning?

- Can the students control and assess their learning behaviour and their results themselves?

- In their self-assessment, do the students also refer to their own objectives, standards, criteria or needs?

- Do I perceive individual students’ progress?

- How do I identify learning problems of individual students?

- How do I observe social interaction in the class?

- How do I keep a record of my observations and assessments of individual students and the class as a whole?

Some questions about the teacher’s learning process:

- How, when and with whom do I reflect on my teaching?

- How do I let my students participate?

- How do I relate my students’ success or failure to my teaching?

- How do I recognise my progress in teaching, and how do I learn as a teacher?

2 - Work file 7: Assessment of teachers

Getting feedback about achievement of students is one of the central principles of school.34 Getting feedback about the quality of teaching is part of professional training. In the same way as we evaluate the learning process and the acquisition of competences, skills and knowledge of our students it is of high importance to get teachers to evaluate their own EDC/HRE teaching.

Without a solid basis of understanding the current situation of teaching it will not be possible to make any recommendations for future improvements or any steps into a further development of teachers’ skills, methods and practices. But how good are teachers in evaluating their own teaching? In fact, the majority of teachers tend to underestimate their students’ forthcoming achievement. Furthermore, they are often not able to shift their methods and style of teaching into a different direction if the need arises. It gets even more interesting when different perspectives of assessment are taken into account: in comparison to all other groups of school assessment (students, parents, school administrators, etc.) teachers’ estimation of their own teaching differs to a great extent from all other formulated opinions.35 Do we have to strengthen teachers in their own beliefs? Or do they have to acquire any new competences in order to take a step back and evaluate their own teaching critically but also realistically?

34. Helmke A.(2003), “Unterrichtsevaluation: Verfahrenund Instrumente”, Schulmanagement, 1, 8-11.

35. Clausen M. and Schnabel K. U.(2002), “Konstrukte der Unterrichtsqualität im Expertenurteil”, Unterrichtswissenschaft, 30 (3), 246-60.

2 - Work file 8: Self-assessment of teachers

For daily school practice, self-assessment of teaching is the most pragmatic and easiest method of assessment. Usually, these kinds of assessment take place automatically among teachers, though not systematically. In most cases, teachers reflect on their teaching whenever they feel it is necessary or according to their own intuition, mostly in cases where they were not satisfied with the outcomes. In order to facilitate these self-reflective processes checklists like the following one could be of some help:

- How have I stimulated the learning process?

- How could I keep up the content interest of the students?

- Were the students led to central problems or tasks?

- Is a focus visible in the taught lesson?

- How many questions did I ask?

- What kind of questions did I ask?

- What kind of questions did the students ask?

- Were the questions related to the problems or the tasks?

- Which contributions triggered which questions?

- Did I listen to the students?

- Were the agreed rules of communication in the class kept?

- How did I react to the students’ contributions?

- Did I repeat students’ contributions word for word?

- Did I use stereotypical forms of reinforcement?

- Was interaction between students stimulated?

- What was the approximate percentage of my contributions?

- What was the approximate percentage of the students’ contributions?

- Were there any students with an extremely high percentage of contributions?

- What was the participation of girls in comparison to boys like?

- What kind of contributions did so-called “difficult” students deliver?

- Did I concentrate on certain students?

- How did situations of conflict arise?

- What was the course of conflicts?

- How were the conflicts dealt with?

- Were the given tasks understood by the students?

- How were the tasks integrated into the process?

- What kind of means of support did I provide?

- How were the results presented?

- How was knowledge, how were insights or findings recorded?

- Other questions?

When using checklists like this, it has to be noted that its use only makes sense if it takes place on the basis of a solid, scientifically founded and empirically secured knowledge about teaching and its effects. In all other cases the mere answering of the questions will lead to an obligatory act and nothing else. Secondly, most of the used checklists are something like a medley of different aspects, but do not represent a full collection of all aspects that could arise in the given lesson. Therefore, when using checklists it is of high importance always to leave them incomplete or to reserve some space for aspects that cannot be foreseen.36

36. Becker G. E. (1998), Unterricht auswerten und beurteilen, Beltz, Weinheim.

2 - Work file 9: Working with journals, logbooks, portfolios37

Reflecting on one’s own teaching with the use of journals, logbooks or portfolios can be an ideal method for self-assessment and a good basis for starting didactical and pedagogical discussions.

Journals

Usually, a journal is constructed in a way that allows some kind of dialogue (with a peer teacher, a colleague from another school, etc.). In a journal the teacher writes about his or her experiences in a diary-like way also expressing his or her personal interpretations and feelings about a certain lesson or a certain behaviour or way of interaction that he or she showed. A journal leaves room for personal remarks and is open to another person’s remarks. The act of going into a dialogue with somebody else and reading another person’s remarks, interpretations and thoughts about something one has already thought about creates a high level of reflection about teaching and learning processes and gives further room for discussion. For reflecting on EDC/HRE lessons it is recommended that the peer-teacher or colleague herself or himself is familiar with EDC/HRE.

Logbook

A logbook is a description of a process without any comments or personal remarks. In a logbook pure facts find their place and can be read again by the teacher and thus create a degree of reflection. In this sense, a logbook can be compared to a diary or a journal without the element of personal interpretation and dialogue. Using logbooks only makes sense when the teacher really goes through them again relatively soon. As a logbook does not include any kind of remarks or interpretation it can become rather difficult recalling certain elements of a lesson which took place a long time ago.

Portfolio

A portfolio for teachers is a collection of materials that have been created and put together by the teacher. It is meant to show the strengths of his or her EDC/HRE lessons as well as his or her identified fields of further development. A portfolio is meant to be an instrument that shows the competences of a teacher in a certain field. In modern teacher training and in-service training portfolios have become a common instrument for qualification. In a second sense, a portfolio is an instrument of reflection. It gives room for criticism and evaluates the effect of lessons, methods, interaction with students, etc. Things that can be included in a portfolio:

- short biography of the teacher;

- description of the class;

- chosen lessons (including worksheets, students’ materials);

- evaluated products of students;

- test results (if there are any);

- personal statements about the teacher’s philosophy of EDC/HRE teaching;

- products such as videos or photos from certain EDC/HRE lessons;

- peer feedback of colleagues who visited EDC/HRE lessons;

- project documentation if the teacher has conducted any in relation to EDC/HRE.

37. The suggested methods in this work file can also be used for students and are common tools in the teaching and learning culture of various European countries.

2 - Work file 10: Co-operative teaching and peer feedback

Without a doubt, co-operative planning of EDC/HRE lessons together with a fellow teacher can be a useful tool for mutual information and co-ordination as well as for the development of class including the evaluation of effectiveness of such processes.

38 Co-operative planning can be restricted only to mere preparation of a lesson (as it is done in the majority of countries) or can lead to joint teaching of the lesson (together through team teaching). Initiating co-operative measures for planning and teaching lessons still has a minor priority in teacher training institutions in a lot of European countries. The culture of leaving each other’s doors open is a process that takes a long time to develop.

It remains an interesting phenomenon that a lot of teachers are hesitant about working closely together with another colleague.

39 Is this the case because good practice models are missing? Is this the case because teachers fear they would have to spend even more time in school? Is this the case because teachers are afraid of being evaluated by colleagues?

As one form of co-operative planning and teaching, collegial group sit-ins in EDC/HRE lessons could be one solution to saving precious time. The following suggestion could act as a guideline:40

| Group size: | Three teachers visit each other twice every half year (everybody receives two visits and makes four visits – they always go in twos). |

| Organisation: | The three teachers plan the visits together according to the actual timetable in a decentralised way. |

| Subject relevance: | Teachers observe each other’s EDC/HRE lessons. What their core subjects are (or the subjects they used to teach) is not relevant. |

| Compilation of group: | Coming together into a group can happen because of sympathy. This secures a minimum amount of trust. |

| Task of principal: | The principal’s role is to keep track of the minimum amount of visits between them. The principal should not get involved in content questions about teaching issues. |

| Thematic focus: | The questions that can be the focus points of these peer sit-ins can arise out of different interests or relations: a) a teacher wishes to receive feedback to a certain question, b) a new method/activity has been decided or intro-duced and should be evaluated now or c) pedagogical principles (for example, formulated in the school’s programme or profile) should be evaluated. |

There are several reasons for adding the element of peer feedback and joint lesson observation and analysis to co-operative planning of teaching. Observing colleagues teach EDC/HRE will add positively to gain more insight into one’s own teaching of this subject. Not only does it act as a tool for diagnosis, but also as a tool for improving one’s own styles and methods.

These are the reasons for this:41

- Learning how to teach is more effective in a real-life class than in joint reflection or a hypothetical, real but not experienced class.

- There are many details which cannot be easily explained when talking about a lesson such as action routines, body language, mimics, behaviour of communication, etc.

- Changing the perspective and taking a more distanced view on a lesson allows viewing of one’s own teaching.

- Observing a lesson unburdens oneself from taking action. It is possible to perceive more details and to receive more space for reflection.

- It is possible to take a number of suggestions out of every lesson viewed for one’s own teaching. The variety of personalities and teaching styles can be an interesting source for impulses which a teacher does not receive on the job after pre-service teaching was completed.

- Observing class and all elements of planning and reflection involve the discussion of didactical and methodical questions and are part of school development which has its starting point at the level of the teacher.

38.Helmke A. (2003), “Unterrichtsevaluation: Verfahren und Instrumente”, Schulmanagement, 1, 8-11.

39. Ibid.

40. Klippert H. (2000), Pädagogische Schulentwicklung. Planungs- und Arbeitshilfen zur Förderung einer neuen Lernkultur, Beltz, Weinheim.

41. Leuders T. (2001), Qualität im Mathematikunterricht der Sekundarstufe I und II, Cornelsen, Berlin.

2 - Work file 11: Assessment of EDC/HRE in schools

Democracy is not an automatic mechanism. Democracy is on the one hand a historical achievement in old democracies and on the other hand a result of a long-lasting process which depends on the specific situation in a country. Democratic attitudes are not given by nature but have to be acquired by every single person through experiences in social contexts, in family and in school. Democracy cannot only be learned in EDC/HRE lessons. Democracy has to unfold itself in the various informal and formal structures of a school. Therefore, school has a key role for a stable democratic society. Furthermore, “a democratically structured and functioning school will not only promote EDC/HRE and prepare its students to take their place in society as engaged democratic citizens: it will also become a happier, more creative and more effective institution”.42

Schools can be assessed using certain criteria to identify the quality of EDC/HRE teaching as well as the degree of lived and practised human rights values and democracy in the school. This can be done using self-evaluation practices.

For evaluating EDC/HRE in schools one needs indicators which reflect different areas of expression. These three main areas are:43

- curriculum, teaching and learning;

- school climate and ethos;

- management and development.

Furthermore, these indicators present EDC/HRE as a principle of school policy and school organisation, and as a pedagogical process.

In this volume we suggest instruments and tools for the self-evaluation of a school, involving all participants of school, not only external evaluators. Self-evaluation in this context also means viewing evaluation as the starting point in a process of improvement, not as an end to something that has happened.

For a more detailed description of measuring a school in terms of democratic school governance please see work files 12 to 18.

42. Council of Europe (2007), Democratic Governance of Schools, Strasbourg, p.6.

43. Council of Europe (2005), Democratic Governance of Schools, Strasbourg.

2 - Work file 12: Quality indicators of EDC/HRE in a school

The Council of Europe tool “Quality Assurance of Education for Democratic Citizenship in Schools” includes a set of these indicators divided into subthemes and descriptors which reflect a desired quality of EDC/HRE in a school. These criteria can be used for judgment and evaluation. Applying this will deliver a comparison between the status quo of a school in terms of EDC/HRE and the desired goals.

The table below – part of the above-mentioned tool – can be used for assessing the status quo of EDC/HRE in a school according to quality indicators.44

| Areas | Quality indicators | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| Curriculum, teaching and learning | Indicator 1 Is there evidence of an adequate place for EDC/HRE in the school’s goals, policies and curriculum plans? |

|

|

Indicator 2 Is there evidence of students and teachers acquiring understanding of EDC/HRE and applying these principles to their everyday practice in schools and classrooms? |

|

|

|

Indicator 3 Are the design and practice of assessment within the school consonant with EDC? |

|

|

| School ethos and climate |

Indicator 4 Does the school ethos adequately reflect EDC/HRE principles? |

|

| Management and development |

Indicator 5 Is there evidence of effective school leadership based on EDC/HRE principles? |

|

|

Indicator 6 Does the school have a sound development plan reflecting EDC/ HRE principles? |

|

(Council of Europe, Democratic Governance of Schools, 2005, p. 58)

44. When the tool was developed in 2005, indicators in the table above were only described as EDC indicators. The extension to EDC/HRE was added to the table for this volume.

2 - Work file 13: General principles for evaluating EDC/HRE

“EDC/HRE is a dynamic, all-inclusive and forward-oriented concept. It promotes the idea of school as a community of learning and teaching for life in a democracy, which goes far beyond any particular school subject, classroom teaching or traditional teacher-student relationship” (Council of Europe, Democratic Governance of Schools, 2005, p. 80).

Values, attitudes and behaviour

As pointed out in Part 1 of this volume, EDC/HRE is primarily concerned with changes of values and attitudes – and behaviour. As in all evaluations – be it students, teachers or schools – assessing dimensions like values and attitudes is extremely difficult as it bears the risk of a very subjective interpretation. Moreover, values and attitudes not only express themselves explicitly through direct behaviour but are included implicitly in the way a school works, communicates and organises itself.

How to collect data

Evaluating EDC/HRE in a school can be done in various ways. The EDC/HRE indicators only provide the general framework for developing the different ways of collecting data or for defining the different methods to be used for getting information.

For this, the following questions can be helpful (ibid., p. 81):

- What: What Information and evidence is to be looked for?

- organisation of the school

- dominant values in the classroom

- understanding of key concepts

- relationships of authority, etc.

- Where: Which EDC/HRE learning setting does the relevant indicator/subtheme refer to and where can evidence be found?

- class teaching

- morning assembly

- group work within EDC/HRE class

- school celebration

- project week, etc.

- Material: Which documents will provide the necessary information?

- school policy document

- school curricula

- school statute

- students’ charter

- teachers’ code of ethics, etc.

- Who: Which persons/groups of stakeholders will provide the necessary Information?

- students

- teachers

- parents

- local administration

- NGOs, etc.

- How: How are data to be collected, which method is going to be used

- questionnaire

- focus group

- discussion

- individual interviews

- observation, etc.

2 - Work file 14: Guidelines for self-evaluation of schools

When a school decides to go through a self-evaluation in terms of EDC/HRE it has to be aware of the fact that this will take a longer period of time, maybe even a school year. This may also be a challenging period which involves many different steps and activities.

The following list, taken from the tool “Quality Assurance of Education for Democratic Citizenship in Schools” (Council of Europe, Democratic Governance of Schools, 2005, p. 73) might be of help in order to remember the main guidelines:45

- raising awareness of all stakeholders about the need for and process of self-evaluation of EDC/ HRE as a means for personal, professional and school improvement;

- making sure that all stakeholders are informed about the evaluative framework in EDC/HRE and its purpose;

- selecting the most appropriate approach for self-evaluation in consultation with a broad range of stakeholders and experts;

- designing valid and reliable evaluative tools (such as questionnaires, interview questions) with the assistance of experts from education research institutes or teacher-training facilities;

- preparing school staff and other stakeholders for evaluation, including their training in the use of evaluation tools; and

- creating a climate of truthfulness, honest reflection, trust, inclusion, accountability and responsibility for outcomes.

|

|

45. When the tool was developed in 2005, the guidelines were only described as EDC guidelines. The extension to EDC/ HRE was added for this volume.

2 - Work file 15: Involving the different stakeholders in evaluating EDC/HRE in a school

When a school decides to go through a self-evaluation, good organisation is needed. Ideally, there should be one person responsible for steering and keeping the overview of the whole process. In most cases this will be the school principal or another person clearly appointed for this task. The responsible person has to be aware that guiding this process will need a high degree of co-ordination and facilitating, rather than top-down leadership. As pointed out in the guidelines for self-evaluation of schools (Work file 14) a self-evaluation process should not be hindered by threatening teachers or students with aspects of power or control.

Therefore, a participatory and collaborative approach has to take place (Council of Europe, Democratic Governance of Schools, 2005, p. 74).

The following recommendations conclude the most important facts when involving the different stakeholders.

Setting up an evaluation team

Seven to nine people form the evaluation team. This could include the school principal, one or two teachers, one or two student representatives, a school-based adviser (in some countries this is a pedagogue or a school psychologist), one parent, one local community representative (or NGO representative) and one representative from a research institute or a teacher training institution.

The tasks of the evaluation team are as follows (ibid., p. 75f):

- prepare evaluation tools;

- provide training of school staff in evaluation techniques and the use of evaluation instruments in EDC/HRE;

- provide information and counselling for evaluators and stakeholders throughout the process;

- monitor the implementation of evaluation tools;

- analyse and interpret the findings in co-operation and consultation with a broad range of stakeholder groups and outside experts;

- prepare different forms of reports for different groups of stakeholders;

- receive and analyse the stakeholders’ comments and suggestions upon their review of the reports.

Important note: generally, the opinions of the different stakeholders should be sought and compared (for example, through parallel questionnaires). Essential in this context are the views of the students in terms of acquisition of EDC/HRE competences such as self-reflection, critical thinking, responsibility for improvement and change (ibid., p. 77). What has to be considered by the evaluation team is the phenomenon of “politically correct” answers given by students in the teaching and school context. Through clearly defining the methods used, this can be somewhat reduced (peer-interviews, very open questionnaires, undisclosed names, confidentiality, etc.).

2 - Work file 16: Governance and management in a school46

A school can also be measured by looking at the way EDC/HRE processes are reflected in the way it is governed. In this respect the term “democratic school governance” is used. In this context two kinds of processes are relevant and have to be distinguished from one another:

| Governance | Management | |

|---|---|---|

| Openness of school and educational systems |

Technical and instrumental dimensions of governing |

|

| We negotiate, persuade, bargain, apply pressure, etc., because we do not have full control of those we govern. | We instruct and order because we think we have strong legitimate power to do so. |

Management, therefore, describes the organisational aspects and technical as well as instrumental dimension in a school or educational system. Through introducing more and more open processes in schools which are characterised by different needs and interests, the term “governance” is used (Council of Europe, Democratic Governance of Schools, 2007, p. 9).

The benefits of democratic school governance can be summarised in the following points (ibid., p. 9):

- to improve discipline;

- to reduce conflict;

- to make school more competitive;

- to secure the future existence of sustainable democracies.

46. For evaluating a school in terms of EDC/HRE we have presented indicators in Work file 11.

2 - Work file 17: Focus on democratic school governance

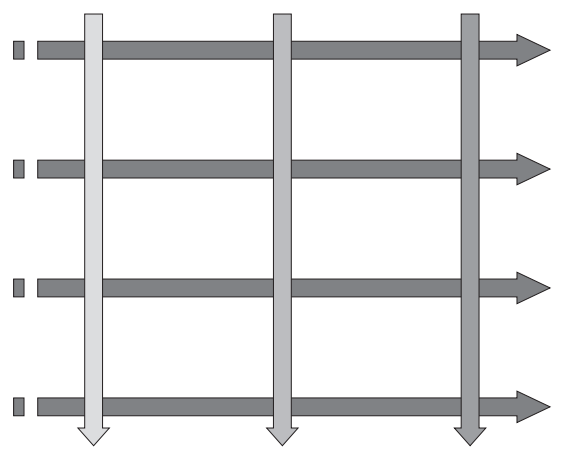

For assessing the status quo of a school with regard to EDC/HRE practice and its relation between theory and practice or between policy and lived democracy we suggest the following matrix (Council of Europe, Democratic Governance of Schools, 2007).

Every school encompasses three main principles in connection with EDC/HRE. These are:

- rights and responsibilities;

- active participation;

- valuing diversity.

In every school there are also key areas where these principles are shown. These are:

- governance, leadership and public accountability;

- value-centred education;

- co-operation, communication and involvement: competitiveness;

- student discipline.

As the following matrix shows, in all key areas different levels of expression of the key principles can be looked at.

| Rights and responsibilities | Active participation | Valuing diversity | |

| Governance, leadership, management and public accountability |  |

||

| Value-centered education | |||

| Co-operation, communication and involvement | |||

| Student discipline | |||

For detailed understanding and use of this matrix the tool “Democratic school governance” will give further information (www.coe.int/edc).

2 - Work file 18: How to analyse and interpret EDC/HRE evaluation results

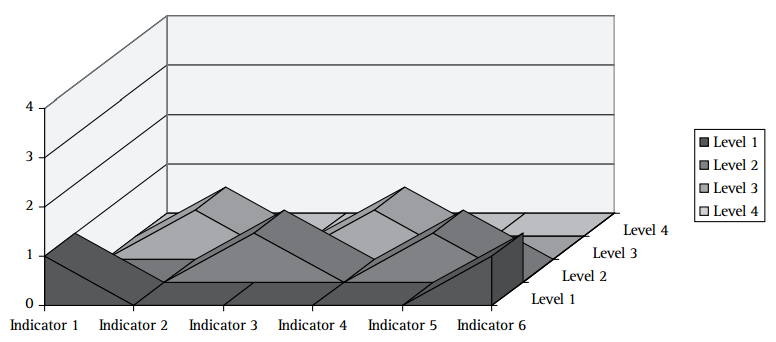

There are many ways to analyse, categorise and interpret evaluation results. When using the set of quality indicators for EDC/HRE suggested in Work file 12, one of the most effective and easiest ways is to start identifying strengths and weaknesses in EDC/HRE. The Council of Europe suggests using a four-level scale for this purpose and thus basing each indicator according to this scale (Council of Europe, Democratic Governance of Schools, 2005, p. 88):

- Level 1 – significant weakness in most or all areas;

- Level 2 – more weaknesses than strengths;

- Level 3 – more strengths than weaknesses;

- Level 4 – strengths in most or all areas and no significant weaknesses.

One possible way to present the results out of such an analysis is using diagrams which show the overall performance in EDC/HRE but also list the different indicators. The example below of a fictional school illustrates this:

When trying to come to a conclusion, this should cover four basic areas (ibid., p. 91):

- the school’s achievement in EDC/HRE in general;

- the school’s position on each quality indicator;

- the most successful and the weakest aspects of EDC/HRE in the school;

- the most critical points that may threaten further development of EDC/HRE in a school.

You are reading Volume I

You are reading Volume I